Manhattan is looking at strategies to fund multiple projects the city has in the works following the recent sales tax ballot question failure in November.

Voters rejected a 0.3 percent sales tax hike 4,187 to 3,359 that Manhattan officials hoped would help cover the costs of projects including improvements to the levee, Aggieville redevelopment, reconstruction of the Manhattan Regional Airport runway, street and sidewalk overhauls around Kansas State University and a new city maintenance facility. The estimated price tag comes in at $170 million, with a gap of $70 million in funding if the city wishes to complete all of the projects.

“These six major projects have been a culmination, really, of close to a decade worth of work,” says Deputy City Manager Jason Hilgers.

Administrative staff Tuesday presented to Manhattan City Commissioners what the plethora of projects’ impact could be if funded through utility funds, sales or property taxes — or a mix of the three funding sources.

Many of the projects leaned on utility dollars to some degree, which Mayor Pro Tempore Wynn Butler urged against. He said using utility money for non-utility capital improvements is “dishonest” and amounts to a hidden tax to avoid raising property tax.

“People are getting upset about those water bills,” said Butler. “Every year, what’s our projection? Go up 3 percent — now we want to add [and]make it 3.7 [percent]because we’re going to build this stuff. I’m not really pleased with that.”

He further said delaying projects that can wait may be necessary if funds aren’t available without increasing taxes. Commissioner Linda Morse agreed on that point.

“And because we can stagger some of them, […] as Wynn indicated,” said Morse. “It seems to me that that staggering will allow us some breathing room.”

Commissioners issued no votes on funding plans or to move forward with any projects at the meeting.

Project Options

Manhattan is responsible for $13.4 million of the $33 million levee project. One option presented Tuesday would be to fully fund debt service through a surcharge on storm sewer customers — a $6.14 monthly surcharge would cover a ten-year repayment plan and a $3.60 monthly surcharge would cover a twenty-year repayment plan.

Another option would be to fund 70 percent of the project with the surcharge plus 15 percent each through water and wastewater rate increases. Under this plan, a $4.31 monthly surcharge would cover a ten-year repayment plan and a $2.52 monthly surcharge would cover a twenty-year plan — coupled with one-time increases of water and sewer rates hikes from 3 to 3.75 percent.

Funding the project solely through property tax would require a mill levy increase of 1.3 to 2.6 mills depending on the repayment plan.

The runway project’s local share is estimated between $4 million and $8 million depending on whether the FAA agrees to provide federal dollars to reconstruct the runway at its current 150 foot width rather than a reduced 100 foot width. Funding the project with property tax will cost between $350,000 and $600,000 per year if the project comes in at $4 million and between $716,000 and $1.2 million if it comes in at $8 million. That impact in mills ranges between about 1.25 to 2.25 mills. Staff also noted the property tax impact could be mitigated with economic development dollars if the commission chooses to go that route.

The joint maintenance facility project is estimated at $13 million — including offsetting revenue captured from sales of current maintenance facility properties. Staff laid down a plan that would 30 percent of the annual debt service from the water and wastewater funds, 26 percent from the stormwater fund, and 7 percent from both sales-tax supported special parks and recreation and special streets and highway funds.

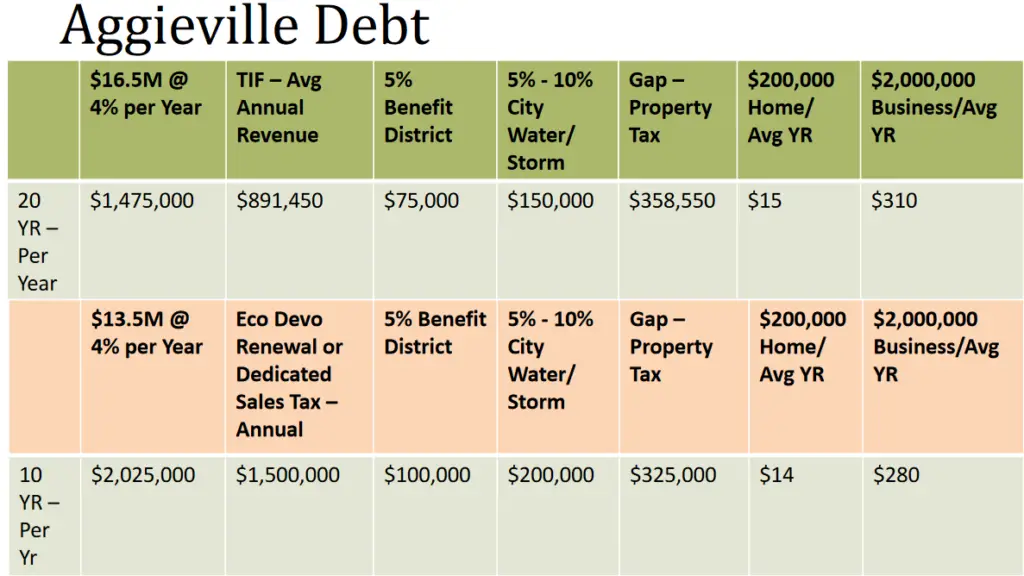

Streetscape and utility revamps as well as the construction of a new parking garage in Aggieville have an estimated price tag of $30 million. A tax increment finance district will generate approximately $12 million in revenue for the projects, leaving an $18 million gap in funding. Manhattan is eyeing a mix of economic development funds, utility dollars, and property tax to fill the gap along with a 5 percent special assessment to business owners through a new benefit district.

Hilgers also stated they are looking into the possibility of using new market tax credits to help the funding situation as well. The Treasury Department’s CDFI has offered new market tax credits since 2003. Through the program, investors provide capital to Community Development Entities to put into qualified community projects and receive credits in return. Hilgers says Manhattan stands to gain 18 to 22 percent of the $16.5 million planned for parking garage construction as well as Laramie and 12th Street improvements.

“There’s billions of dollars worth of projects that have been funded across the country over the last 15 years,” says Hilgers. “This could be one of them.”

Mayor Usha Reddi was in favor of continuing the application if they think there is a 50 percent or more chance it will work out.

“Otherwise that is a lot of staff time and we have so many things going on,” says Reddi. “So if you feel like this has a lot of potential, certainly I think it’s in our best interest to pursue it.”

Hilgers said staff is optimistic as they’ve heard renewed interest in investment in the past two weeks.

North campus corridor projects come in at an estimated total price of $43 million, $17 million of which has been committed from Manhattan, K-State, KSU Athletics and KDOT. That leaves a gap of $26 million which jumps up $20 million or more with interest. Options to fill that gap include a renewal of the economic development sales tax, a future dedicated sales tax, or adding the payments to the partially property-tax supported bond and interest fund as old debt retires. Manhattan estimates 4.7 mills of mill levy supported debt will expire in 2020 alone.

A large piece of the puzzle is the renewal of the current half cent economic development sales tax shared by Manhattan and Riley County.

The voter-approved tax has been in place since 2012 and expires in 2022 and generates Riley County $2 million per year and Manhattan $3 million per year — but does not extend into the Pottawatomie County side of the city. If renewed city-wide and independently of Riley County, Manhattan would more than double its annual take-away for an estimated $6.5 million per year.

Commissioner Mark Hatesohl noted the decision isn’t solely theirs due to the shared nature of the current sales tax. Without cooperation, Manhattan and Riley County could submit competing sales tax ballot questions in November.

“We’re going to be butting heads with the county, potentially,” says Hatesohl. “So we’re going to have to chat with them I suspect.”

He raised the possibility of extending the sales tax solely in the city for another ten years while sharing a portion of the revenue with Riley County. Mayor Pro Tempore Wynn Butler was in favor, saying they could strike an interlocal agreement.

“If we can collect 60, 65 million, we give them what they normally have for roads and bridges and I think we’re still way ahead,” Butler said.

Commissioners held no vote, but discussed the possibility of including the question in this upcoming November’s ballot due to higher numbers of voters during presidential elections.

Manhattan administrative staff also discussed the possibility of creating a multi-year strategic plan for the city’s future.

Across all governing bodies, a total of 156.510 mills are levied in the City of Manhattan. Manhattan’s share of that totals 49.798 mills, of which 6.5 mills supports the general fund covering the majority of Manhattan’s personnel costs. Hilgers told commissioners not many 1st class cities in the state operating on that small a budget for services and operations. Additionally, he said that cuts to contractual services, commodities and the 2018 hiring freeze have forced city staff to pull money from reserves and cushions — something he says cannot continue.

“We’re running on razor thin lines — we need a foundation underneath our general fund in order for this organization to deliver the services everybody expects,” says Hilgers. “If we just look at it on an annual basis and we’re just trying to fill a gap for a year, I feel like we’re going to fall short. We’re going to fall short with that governing body and that community in 2024, 2025.”

Hilgers pointed to the example of Lawrence, which divides the city’s budget into four quartiles based on how vital they are to the city and help identify areas that can be cut in down years.

“Having that multi-year or at least having a tiered approach where we’re able to evaluate what it’s going to cost and what those cuts would look like to keep a mill levy flat, to keep a water fund flat, whatever those sacrifices might be […] has been greatly missing,” said Commissioner Aaron Estabrook.

Hatesohl was also on board, saying it could help reduce the necessity to hold five or more work sessions to hash out the city’s annual budget. Butler also expressed interest in such a plan, advocating for what he called “predictable” budgeting.

Mayor Reddi, though, had some pause. She noted that the Riley County Law Board operates on a yearly budget as well, which Manhattan helps fund, so they would need to work with them if they begin budgeting on a multi-year schedule. Reddi was unsure if the plan was necessary as they have a plan of projects and some timelines already in place, Manhattan just needs to set up funding mechanisms.

“I don’t want social services to continually come up as that’s the place we can take money out of,” Reddi said. “When we have a community that is so vibrant, we also have a lot of vulnerable populations that need an extended hand or need a support system.”

Reddi says an annual process also keep the community involved every year.

Hilgers says the discussion can continue in a separate work session on the specifics of a strategic plan and what it can do. The price tag to formulate such a plan ranges from $250,000 to $300,000.