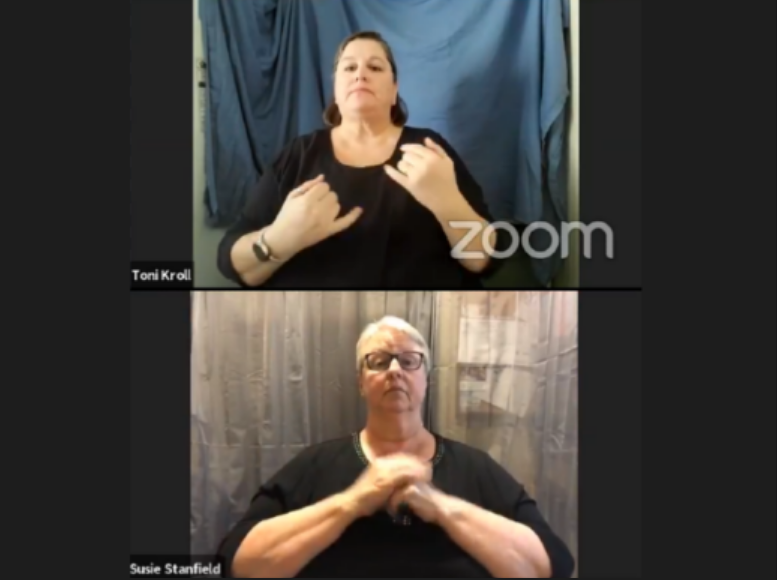

Among a cast of local health, safety and government officials, two area women have also taken center stage to serve a segment of the community during Riley County’s near-daily online COVID-19 updates.

Sign language interpreters Susie Stanfield and Toni Kroll have become familiar faces in those Zoom-conducted conferences, following along with speakers including Health Department Director Julie Gibbs and Assistant RCPD Director Kurt Moldup, ensuring deaf and hard-of-hearing residents of the county and beyond can access the latest official information related to the ongoing pandemic.

Susie and Toni both first gained an interest in sign language as youths through experiences with the deaf community and interpreters at church. Those experiences and interactions started the two down roads that led them to their more than 30-year careers in interpreting and deaf education.

“As an early teen a family joined my church and they had a daughter who was deaf, she was my age, and I just started learning signing from her,” Susie says, who began her career in Alabama. “Her mom took me to a couple of classes, I interpreted youth group activities and we went on trips and I kind of acted as her interpreter.”

“Pretty quickly I learned — in fact, by the time I was in 10th grade — I knew that I wanted to work with deaf people, mainly deaf students.”

Susie’s career brought her to Manhattan in the early 90s, here she began working for Manhattan-Ogden USD 383 and did so for 17 years until she began getting contacted by neighboring rural school districts. These districts would often have but one deaf student, Susie says, and were looking for an interpreter to serve them on a contract basis. There, she saw an opportunity to be her own boss and founded I SIGN Consulting, now finishing its 11th year, through which Susie has served students across Riley, Pottawatomie and Geary Counties as well as Chapman High School.

“Several times, we’ll say, I have taken a student from preschool all the way through graduation, working with them every year during that time,” says Susie.

Susie estimates she’s worked with easily more than 100 students in her career locally, saying the best part of her work has been her involvement in a number of “water pump moments” — an allusion to when Helen Keller first caught onto the meaning behind the signs being signed in her hand by teacher Anne Sullivan Macy.

Toni was born in Alabama and raised mostly in Utah, though her family spent some time living in Rochester, New York, home to the National Technical Institute for the Deaf in the Rochester Institute of Technology. The community is also home to one of the largest per capita deaf and hard of hearing populations in the nation, with a total population of more than 42,000 as of a 2012 NTID report.

Toni’s first encounters with sign language were similar to Susie, saying she was “entranced” when she first experienced the language in her Rochester church.

“I would sneak out of my kids’ Sunday School class to go over to the deaf group Sunday School class,” Toni says. “And the teacher would get my mom and then my mom would have to come and drag me back to class.”

Toni fell out of practice for a time, but after a mission trip she returned to live with her parents near Chicago at this point. Once again, church led her back to signing. Toni was studying with the intending of going into the nursing field, but was won over by the sign language interpreter training program and never looked back.

She moved to Manhattan in the year 2000. Here Toni spent a few years eventually working for USD 383, where she met Susie, but says the K-12 education side is not really her forté.

“I’ve always been more of a community interpreter,” she says.

Toni’s career began with Sign Language Associates in Washington D.C., providing services for the Department of Justice, FBI, Equal Employment Opportunity Commission as well as for individuals attending community college classes. She describes her time in D.C. as marked by variety.

“That’s one thing I love and crave is that variety,” Toni says. “I don’t — until the quarantine — sit at home at the same place and do something. I’m going to different places, especially when I was working in the larger cities, different people all the time.”

“A challenge of doing it this way is you have no safety net — no benefits, no health care, no taxes being taken out, so you have to take care of your own taxes.”

Now, she gets called to interpret across the region through word-of-mouth recommendations and existing relationships with the deaf, medical and legal communities.

The two are not only proficient in American Sign Language, but have also worked with individuals that prefer Signing Exact English (sign language that follows spoken English rather than the separate grammar and sentence structure of ASL). There are other forms of sign language preferred by individuals in the deaf community such as cued speech, and Toni says the local community has a good mix of those who use the ASL and SEE dialects.

When COVID-19 was declared a pandemic and actions began being taken locally, City of Manhattan Public Information Officer Vivienne Uccello says it became quickly clear that it would be vital to secure interpreters for the near-daily updates being broadcast online. As Susie and Toni were some of the only available interpreters in a 60 mile radius — “let’s just say it is not a crowded profession,” Susie says — they were obvious choices.

“Thankfully, [Riley County Health Department Director] Julie Gibbs had a relationship with both Toni and Susie and called on them,” says Uccello. “They answered the call very quickly and said absolutely, whatever you need us for we’ll be there to provide.”

The work and preparation of the two long-time interpreters has impressed Uccello, both of whom often spend many hours outside of their service to study the latest information on the pandemic released at the local, state and federal level in addition to keeping up to date on the latest advice and recommendations from the deaf community.

“For this response in particular, the more the public knows about what the threat is, what’s expected of them, what the requirements are, what they need to do to maintain their health and safety — for themselves, their family and the entire community — that’s been essential,” says Uccello. “Without the means to reach an entire section of the population, we would be putting not only them, but kind of the entire community at risk if they didn’t have access to the information that they needed.”

Toni and Susie have regularly received feedback that the community appreciates the access they provide — and not just in Riley County. Susie says there are deaf and hard of hearing residents from five different counties that tune into Riley’s near-daily briefings to stay up to date on the latest numbers and information related to the pandemic.

“They know the numbers may be a little different, but, you know, the stay-at-home order came down from the governor’s office,” says Susie. “It’s a state-level order and so having access to that information lets them know some of those state-level decisions that are also going to apply to their county regardless of which county that is.”

In an interview with the Daily Moth, a news agency that delivers information entirely through ASL, World Federation of the Deaf President Dr. Joseph Murray indicated that nearly 100 countries provide sign language interpreters during public pandemic briefings. In countries without such access or in more rural areas, Murray signs that deaf communities rely on information in videos online and on social media (if that access is even possible) and deaf associations often have to take it upon themselves to spread vital information in an accessible format.

Toni and Susie also note that in the absence of services such as they provide, it is possible for misinformation or misunderstandings to spread within the deaf and hard of hearing community. They say not every deaf person is as proficient in English as they are with ASL or another sign language, and that context and understanding can get lost in subtitles or printed reports.

“I had one woman from Junction City who I talked with recently and she was like ’10 people have died in Junction City,'” Toni says. “And I was like, I don’t think that’s true.”

Toni says she was able to direct her to the daily briefings from Riley County and get her connected with official information, something Susie says technology has assisted with greatly — but it hasn’t solved every problem.

“Let’s just take YouTube, for example. You can find a lot of news things on YouTube and you can click the closed caption button and a lot of times the captioning will show up,” says Susie. “But it’s my experience that a lot of times that captioning is not correct […] or it doesn’t have grammar built into it.”

“That definitely adds to a lot of the mis-messages and the misunderstanding of what’s going on because they just don’t have full access to the information.”

The two both note that news agencies such as the Daily Moth, though, have helped to bridge some of those information gaps.

The two have both had prior experience interpreting for folks during various medical appointments, but like most this is their first pandemic. Just as the hearing public’s vocabulary has grown amid the outbreak, so has sign language.

“COVID-19, this is new,” says Susie. “As hearing interpreters, we look to the deaf community to see what signs they have created for these new terms.”

After agreeing to assist in the briefings, Toni and Susie dove into study to get up-to-date on the latest signs for newly popularized terms — including different signs for coronavirus and COVID-19. The two garner best practices from professional interpreter groups online as well as watching what others like the Daily Moth do.

“Because this is a worldwide situation, there’s a lot of information for interpreters out there,” Susie says. “The deaf community got it out pretty quickly to make sure that all of us had access to the right signs.”

“Actually, a deaf person here in this community taught me the coronavirus sign […] and so then I went online and started looking and seeing, yeah, that’s what people are using,” Toni says. “I was signing pandemic similar to the way I sign epidemic and then I saw somebody […] reputable online that then signed pandemic.”

“And Susie and I have communicated with each other and talked about how are we going to sign [different terms].”

The work outside of the generally half hour broadcasts can be extensive as well, making sure they are up to date on the latest numbers, guidelines, recommendations and orders to ensure they are prepared to go by 4:15 p.m. Not only that, they say the broadcasts themselves require focus in order to accurately process information presented in English and translate it into an entirely different syntax and grammar structure — all on the fly.

Additionally, the job can wear on the body. Toni and Susie both say it’s common for interpreters to experience arthritis, repetitive motion syndrome and carpal tunnel — Toni even reports having had surgery for carpal tunnel — and that eventually the pain can force people into retirement.

But despite the hours of work and the discomfort at times, both say knowing they are providing the community a needed service that is all the more vital at this time keeps them going.

“I don’t want to say I help the deaf people because they don’t really need my help per sé, but I definitely feel like it’s a service that I can do,” Toni says. “I’ve done it […] 30 plus years now and I love it. For brief periods of time I went away from it, but I always come back and I just — it’s fun, it’s exciting, I learn so much.”

“For me, there’s always a little part of […] the teacher in me that just wants to make sure that all of the deaf people in this area have the fullest possible access to any communication that they want to be part of,” says Susie. “And for the most part, the only way that’s going to happen is through an interpreter.”